Over the past two decades, Beijing shifted its international development strategy from a bilateral to multilateral one, building up its influence through traditional global organizations while also launching alternative initiatives. The largest by far is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), an infrastructure development strategy that grew from a vague suggestion to China’s Central Asian partners into a $900 billion initiative—which has sparked the United States and its Group of Seven (G7) partners to build their own alternative.

With US domestic political winds pushing against global leadership, coupled with the climate and COVID-19 crises, China seized an empty space. Despite its obvious shortcomings in dealing with the virus domestically, Beijing has tried to turn this struggle into an opportunity to boost its international influence by flooding the world with medical aid and vaccines. And on climate, it went from blocking key international agreements to being the world’s biggest investor in renewables.

The way China’s new Global Development Initiative (GDI) was announced last September shows how much the country’s status and role in global governance has changed. At the General Debate of the 76th Session of the United Nations (UN) General Assembly, President Xi Jinping was given the floor to state that the world needs to work together to address the immediate challenges threatening the delivery of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) while promoting more balanced and inclusive multilateral collaboration. The declaration was well-received, but it was more of an aspirational call to action than an actual roadmap, since its goals remained purposefully unclear.

In some ways, this is a positive development. The United States and its allies had long encouraged China to strengthen its participation in multilateral organizations in order to move it away from a purely bilateral aid model. And it did: Over the past decade, China has more than quadrupled its discretionary contributions to multilateral development institutions and funds and gained voting shares across nearly all international financial institutions (IFI). Over the same period, US contributions have shrunk.

But there are fears that a growing Chinese presence in multilateral organizations and massive initiatives like the BRI could give Beijing undue influence over the developing world. With the GDI, China wants to lead what it hopes is a new era in development—not only by investing money, but also by leading the conversation. But letting China adopt this leading role means risking the spread of Beijing’s approach of decoupling human rights from governance and, consequently, fueling the rise of autocratic societies in the developing world.

While China’s involvement in international development is beneficial—since alleviating poverty requires all possible resources and help—the West cannot let China lead this dance alone if it wants to preserve democracy and foster true prosperity around the world. This is why it must match China’s investments in IFIs, as well as regaining voting shares and pursuing key leadership positions in those institutions.

International development as an influence-builder

China’s vision contrasts strongly with that of the West. For rich countries and traditional multilateral institutions, international development amounts to assistance provided to poor countries through aid, low-interest lending, and grants. But China sees this as an investment in its own influence—hoping that lending and trade will lead to economic opportunities for both China and its developing partners.

The BRI is the direct application of this vision. Yet with suspicions of debt-trap diplomacy and disappointing returns for local communities, partners began to question whether China’s path to prosperity was the best one. The country’s slowing growth, the drop in domestic demand, and the worsening of the global economic environment sparked suspicions that China needed to adjust its model. The GDI is here for that.

Today, China holds influence in traditional multilateral institutions such as the World Bank and the UN Development Program, which are the best platforms to advance its plan. No other country has raised its contributions like China has over the past ten years—and the developing world is watching. Like the BRI in its infancy, the contours of the GDI are not quite defined, but China’s intentions are clear: Projecting soft power by leading the conversation about global governance. Xi wants his country to be the leading voice pushing for multipolar global governance, in which smaller countries gain a stronger voice (and, in turn, reinforce Chinese influence).

This message resonates within the developing world. The West’s failure to deliver vaccines to poor countries has increased resentment toward US-centric global governance, and while the West remains focused on the war in Ukraine, China continues to build its soft power elsewhere. The story being sold—that China is the one that hasn’t forgotten about you—is enticing and already gaining praise within developing countries and international organizations.

In less than a year after its launch, more than fifty-five countries have voiced their support for the initiative—calling themselves the Group of Friends of Global Development Initiative, which hosts working sessions at the UN. Last May, the GDI was discussed at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos. The international community is commending the initiative, even though it does not provide tangible solutions yet.

Indeed, part of China’s vision of international development aligns with that of the international community’s, focusing on issues such as climate and health. But it differs on two essential points: human rights and internet governance—two essential tools to build authoritarian capitalistic societies.

Riches over rights

On the surface, China’s promotion of the GDI seems to emphasize the importance of protecting and promoting human rights, a notion echoed by Xi when he called for countries to make global partnerships more equitable and balanced to achieve the 2030 development agenda. But in reality, China has supported a state-centric approach to development and an unconventional interpretation of human rights, in which it considers economic development itself as a human right, preceding all other rights.

It said so as early as 1993, when China’s delegation to the World Conference on Human Rights that year stated: “For the vast number of developing countries to respect and protect human rights is first and foremost to ensure full realization of the rights to subsistence and development. The argument that human rights are the precondition for development is unfounded. When poverty and lack of adequate food and clothing are commonplace and people’s basic needs are not guaranteed, priority should be given to economic development. Otherwise, human rights are completely out of the question.”

While China’s development model has been heavily focused on rapid growth, thanks to capital accumulation and investment, high savings and low consumption rates have made that growth unsustainable and have resulted in distortions in the economy. China has one of the world’s highest national saving rates, which is explained by the government’s promotion of low consumption and high precautionary household savings (which in turn results in high levels of investment and growth). Officials have effectively stimulated savings by vacating the one-child policy and spending little on a number of fundamental human rights, such as health care, education, and other forms of social assistance.

China’s significant urban transition has also resulted in excluding its rural areas from opportunity. Millions of children were left behind by China’s urbanization, experiencing poverty, lack of quality education, poor health, and deteriorating living conditions that are worse than in many other parts of the world. Co-author Yomna Gaafar witnessed such challenges when she volunteered in 2017 as a teacher for left-behind children in China’s rural in Jiangxi Province—where there was a shortage of resources and overcrowding. She witnessed students parenting themselves and even their younger siblings, since their parents had to leave to seek work in major cities in response to China’s rapid economic growth.

Today, China has changed its stance on human rights from a defensive to a proactive one. With the GDI, China is attempting to break Western hegemony over global human-rights governance. Leaders from countries that struggled to find a way out of poverty through traditional systems are offered a quick “people-centered” development model centered around wealth and material goods. But it is doubtful that a country widely criticized for seeking to effectively imprison an entire ethnic minority is truly planning on changing its ways.

Don’t let China take the lead

It is inevitable that China will play a dominant role in global governance. This is why the West must take action now to mitigate the propagation of Chinese ideology in the developing world.

First, it needs to seize the initiative in attracting investments by cutting down on stifling bureaucracy. International lenders and investors should compete with the terms set by China so that the developing world no longer sees Beijing as a better business partner. One could hope that the Biden administration will keep that in mind when implementing its Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII).

Second, the international community should focus on what actually works. For this purpose, the Atlantic Council has built the Freedom and Prosperity Indexes, which offer lessons for policymakers to help understand what matters most for development.

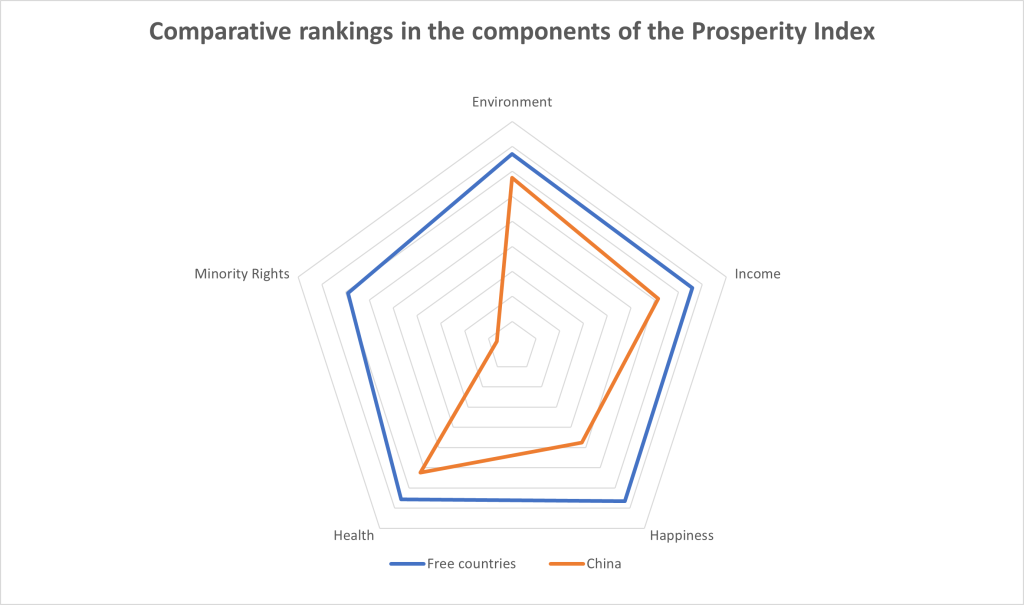

China has lifted many of its people out of poverty. But the main lesson is that true prosperity is not just gross national income per capita; freedom is still the best way to achieve prosperity. And on key components, such as political freedom (where it ranks 158 out of 174), property rights, and investment freedom, China underperforms when compared to free countries.

The five axes represent the five indicators forming the Prosperity Index. The center point represents the rank of 174, the worst possible performance. The outer line represents a rank of one, the best possible performance on each indicator.

International organizations, development agencies, and nongovernmental organizations should continue to endorse economic, political, and legal freedoms as the best path to prosperity despite China’s influence. The United States and its allies and partners in the free world should urgently develop a strategy to mitigate Chinese global influence. The West tends to forget how powerful a tool international development can be to structure global governance.

Through its PGII, which for now is a mere answer to China’s BRI, the United States is proving itself to be several steps behind. Infrastructure and investments are only one part of the puzzle. However daunting, competing with China where it is the strongest—infrastructure development—is a necessary step toward courting potential partners in the developing world.

But it must be also complemented by a clear plan for how to regain the trust of developing countries. Part of that means providing support to vulnerable countries during crises, and, for instance, not allowing Americans to simply throw away COVID-19 vaccines (which opened an avenue for China to step in). Then there is leading by example: When Europe requalifies natural gas as sustainable energy, it loses legitimacy to discuss climate policies. And when it does, the leader of renewables—China—happily grabs the seat.

When navigating a generation-defining war and dealing with global inflation, all this might seem like a low priority. But the game of influencing global governance is a long one. To start, the West must play a more active role in multinational organizations, such as IFIs, in a way that would balance out China’s growing influence within those platforms. It is a low-cost effort, but one which will prove essential in the long run.

Joseph Lemoine is the deputy director of the Atlantic Council’s Freedom and Prosperity Center.

Yomna Gaafar is an assistant director at the Freedom and Prosperity Center.

Further reading

Tue, Jan 11, 2022

The US risks losing its influence in the Horn of Africa. Here’s how to get it back.

New Atlanticist By Gabriel Negatu

Evolving crises in Ethiopia and Sudan have exposed Washington’s lack of a clear and coherent policy for the region.

Fri, Apr 1, 2022

Biden has laid out a new vision for democracies to succeed. Here’s how to implement it.

New Atlanticist By Ash Jain

Winning the struggle against autocracy won't be easy. But unless the world’s leading democracies are strategically aligned and committed to act in the long term, success may prove elusive.

Wed, Jun 8, 2022

Don’t let digital authoritarians lead the way in connecting the world

New Atlanticist By Jochai Ben-Avie

The democracies of the world aren't stepping up enough to connect billions of unconnected people. Here's what they can do.

Image: Indonesian President Joko Widodo greets Chinese President Xi Jinping during their meeting in Beijing, China, on July 26, 2022. Photo by Laily Rachev/Indonesia's Presidential Palace/Handout via REUTERS