September 20, 2022 —  Editor’s note: This story was co-published with The Guardian.

Editor’s note: This story was co-published with The Guardian.

In July 2019, China rolled out the carpet for Bangladeshi prime minister Sheikh Hasina. Flown to Beijing by the Chinese government, she was greeted with an honor guard and banquet and received by both President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Li Keqiang. Three days later, she returned to her capital, Dhaka, with nine agreements worth billions of dollars to build power plants and provide other development assistance.

Hasina’s short visit benefited both countries. Big new infrastructure projects would help lift living standards in Bangladesh, but also enable China to strengthen its influence on its fast-growing neighbor of more than 160 million people.

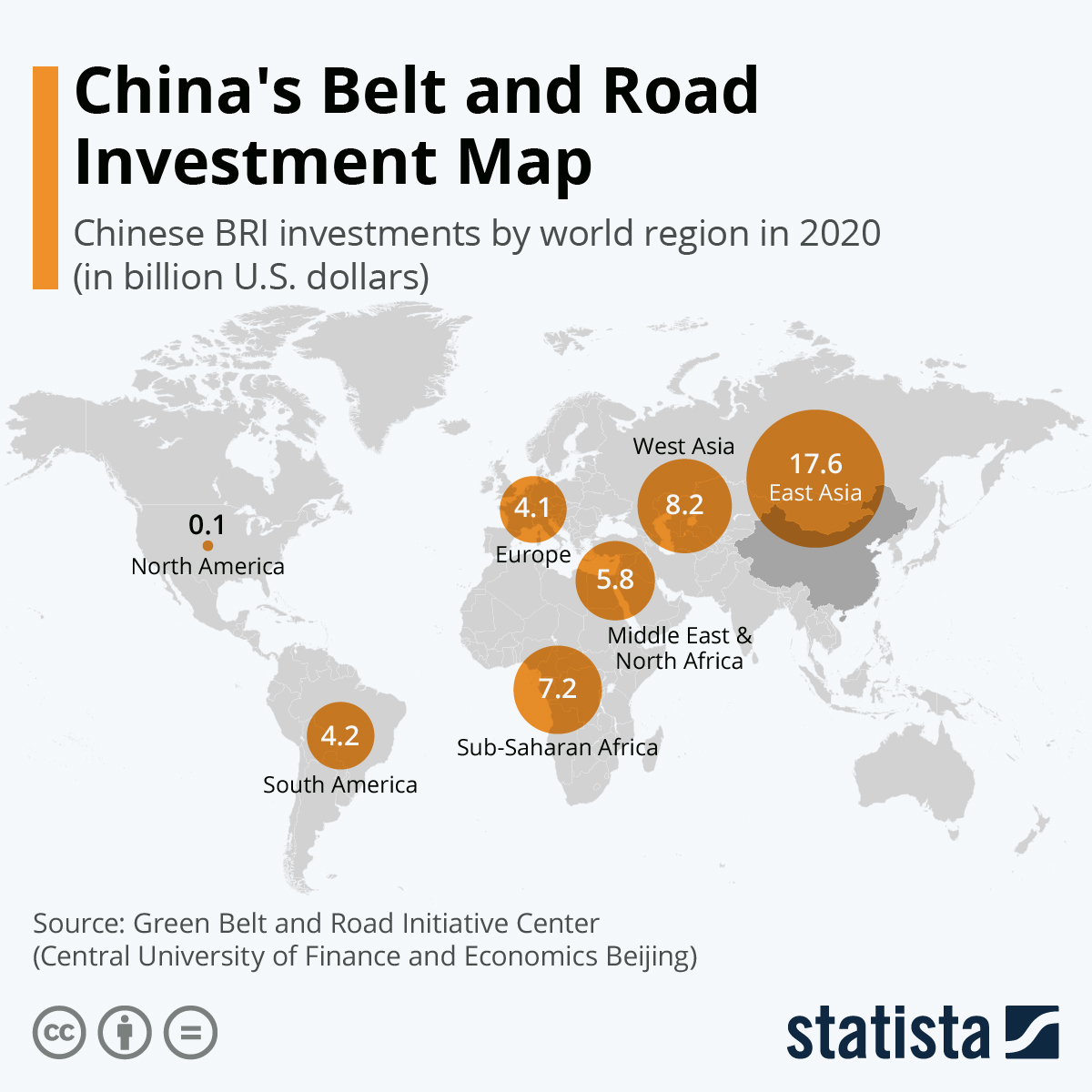

Those loans and agreements made up one very small part of China’s Belt and Road initiative (BRI) — the world’s largest infrastructure program since the U.S. Marshall Plan helped rebuild Europe after World War II. Launched as a President Xi flagship project in 2013, it involves China flooding the world with investments to construct a trillion-dollar-plus modern “Silk Road” network of many thousands of individual projects along major transcontinental corridors spanning Asia, Africa and eastern Europe.

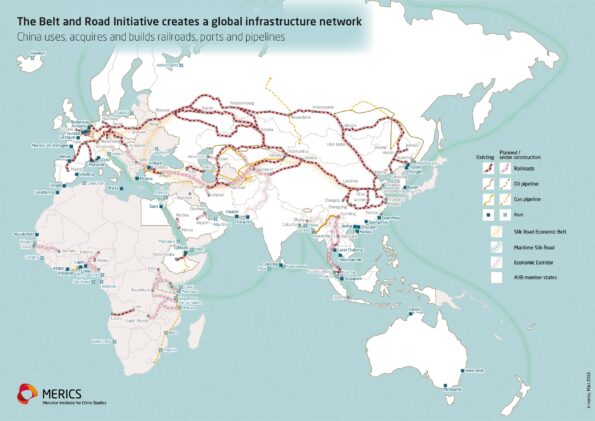

Between 2000 and 2017, China invested some US$843 billion in 165 countries and more than 13,000 projects, many of them related to the BRI. They include high-speed railway lines, coal and hydropower plants, ports, roads, bridges, and tourism developments. Chinese money has flooded in for dams, hospitals, mines, pipelines, IT cables, and the construction of new cities and parliament buildings. The bulk has gone to transportation and power projects and, according to a report by Morgan Stanley, by 2027 China’s total investment could approach as much as US$1.3 trillion.

But while many world leaders have welcomed BRI as a way to raise cheap loans and receive grants not available from the World Bank or wealthy countries, they are becoming more cautious as the full environmental and social costs of China’s loans become apparent and their countries risk being swamped with debt.

Biodiversity Threats

Many BRI projects have involved pushing roads and rail freight lines through some of the world’s biologically richest places. In one study, the World Wildlife Fund and HSBC warned that BRI could impact many critical biodiversity spots, endangering 265 threatened species such as Amur tigers, oriental white storks and giant pandas.

University of Queensland researcher Divya Narain, lead author of a study published in Nature about biodiversity safeguards for BRI, says the initiative is potentially the “riskiest environmental project in history,” poised to transform global transport and trade. “It will have extraordinary impacts on the environment as its corridors and other projects crisscross some of the most pristine and vulnerable ecosystems in the world,” she says.

Narain has calculated from the World Bank BRI database of projects that some 33 transport mega-projects, including 9,500 miles (15,000 kilometers) of rail and road, are proposed or planned, and that 48 major hydropower dams are planned or under construction under BRI. And many finished projects have already been hugely damaging, Narain says.

A giant dam on a Mekong River tributary in Cambodia and a major rail line running from China to Laos both led to deforestation and the forced eviction of thousands of families. Coal power plants in Pakistan, Kenya, Indonesia and Serbia have sparked protests over pollution, and road and rail projects in Malaysia and elsewhere have plowed through fragile ecosystems. A railway in Kenya that crosses Nairobi National Park and is planned to extend into Tsavo National Park, one of Africa’s most important wildlife reserves, has been strongly opposed by conservationists.

Source: Statista

Source: Statista

Much damage has been done because Chinese funds for BRI projects, unlike loans attached to World Bank or most rich countries’ aid programs, lack restrictions meant to protect biodiversity, says Narain. Chinese companies and financial institutions working abroad have only to adhere to the “host country principle,” which means they often only have to comply with local environmental and social regulations.

Narain found that just one of 35 Chinese financiers identified as backing a series of projects demanded any safeguards to protect nature. She concluded that unless this changed, BRI infrastructure projects would remain damaging.

A major study of 13,427 China-funded projects published by AidData at William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, found that more than one in three projects had encountered “major implementation problems,” such as corruption or environmental protests. A growing number of projects, the study reported, have been canceled, downsized or mothballed, including a new airport in Sierra Leone and large port expansions in Tanzania and Myanmar.

Strong backlash to BRI has come from critics in wealthy countries who point out that China is the world’s largest funder of heavily emitting coal power stations. According to a 2019 report by the Ohio-based Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, China was funding via its BRI projects more than a quarter of all new coal power plants being developed elsewhere — even as the World Bank and wealthy countries were pledging to end virtually all coal financing.

Green Silk Road

Stung by criticism that BRI threatened UN climate goals, China has announced a flurry of new initiatives to rebrand BRI as a “green silk road.” In April 2019, President Xi stated that the BRI must embrace sustainability “to protect the common home we live in.” In 2020, he said that China would aim to peak carbon emissions by 2030 and become carbon neutral by 2060.

In 2021, at the UN General Assembly, Xi pledged to end support for new coal power projects abroad. This was followed in March 2022 with a new directive from China’s National Development and Reform Commission that appeared to commit Chinese banks and developers to raise construction and financing standards. A “green” BRI should be in place by 2030, while by 2025 environmental risk prevention of BRI projects would significantly improve, the new directive said.

But analysts like Narain point out that the new guidelines mean little, as BRI is not governed centrally and no Chinese bank that is financing BRI projects has any binding requirements to protect biodiversity or lower emissions overseas. “These guidelines remain aspirational and do not require banks to put mandatory environmental standards in place,” she wrote in an email. “Unfortunately, this is still the case.”

Additionally, BRI’s vast scale and reach, and the ease with which loans for major projects have been approved by Chinese state banks, have led to accusations that it is a geopolitical instrument of foreign policy meant to make China the most powerful country in the world under the pretext of infrastructure construction.

Between 2000 and 2017, China invested billions of dollars on thousands of projects — including high-speed railway lines, coal and hydropower plants, ports, roads, and bridges — in countries around the world, many of them related to the BRI. Map by Merics. Click map to expand.

Sources in China accept that BRI projects often bypassed environmental regulations and damaged local biodiversity, especially in the early days. But as rivalry with the U.S. over climate and global leadership has grown, China has become increasingly attentive to green standards.

“At BRI’s peak, China was running around signing [memorandums of understanding] on projects which should never have been constructed,” says Scott Morris, a senior fellow at the Center for Global Development in Washington and author of a report on a major China–Laos BRI rail project. “Now I think that China, at a serious level, is doing a rethink. They are facing political backlash and financial risk associated with environmental harm. A lot of local communities [around the world] are unhappy. They are rethinking the BRI model,” he says.

“Issuing new guidances will not translate immediately into green practices,” says Christoph Nedopil Wang, founding director of the Green Finance & Development Center and associate professor at Fudan University in Shanghai.

“Guidance is not the same as law, and developers do not necessarily understand. [Nevertheless] China is genuinely trying to bring its construction and financing standards up to another level,” he says. “I am 95% certain that no more coal power plants will be built by China. There will be exceptions, but globally there is no support now for coal. All fossil fuel [projects] are being phased out. Hydro dams will be phased out. Renewable energy is moving from the fringe to the core of BRI. It is accelerating.”

But biologist William Laurance, director of the Centre for Tropical Environmental and Sustainability Science at James Cook University in Cairns, Australia, remains skeptical. “BRI will still have a major impact on ecosystems: China has said that it will be low carbon, green and sustainable, but it is anything but that,” he says. “New roads will still decimate forests, transport routes will still destroy biodiversity on a grand scale. China says it will follow environmental guidelines, but history has shown these protections are nonexistent.”

Despite such suspicions that most Chinese projects will barely be affected by the “greening” of the BRI, the country has not financed any new foreign coal plants under the BRI since the beginning of 2020, and many projects have been canceled or suspended, says the Finland-based Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA).

According to a briefing paper by CREA analyst Isabella Suarez, 15 coal plants that would have produced around 12.8 GW of electricity have been canceled so far, but 18 projects with a combined capacity of 19.2 GW might still proceed because the backers have already secured the permits and financing or they are tied to industrial development. “China may continue to fund or build new coal projects under the Belt and Road Initiative because a loophole means that some projects already planned may go ahead,” she says.

Rival Plan

Earlier this year, the U.S. and other G7 countries, fearing that BRI has enabled China to take the global geopolitical lead by financing hard infrastructure projects in poor countries, launched a rival plan that aims to invest US$600 billion in the next five years alone. Details of what is called the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) are still vague. But rather than loan countries money to build roads, railways, ports and dams, early indications suggest it will try to counter China’s influence in developing countries by financing “soft” projects such as industrial-scale solar plants, a vaccine manufacturing center in Africa, and digital infrastructure linking Asia and Africa. So far, the U.S. and EU have pledged to raise US$200 billion and US$317 billion, respectively.

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!