Don’t Call It a Global Banking Crisis

This isn’t 2008—but we’re not in the clear just yet.

This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

The near-collapse of the global banking behemoth Credit Suisse, shortly following two high-profile American bank failures, complicates regulators’ efforts to restore confidence in the banking system. It’s also stoking fears of a contagion effect across the financial sector worldwide. Experts say it’s not a crisis—but we’re not in the clear just yet.

First, here are three new stories from The Atlantic:

Swimming Naked

On Sunday, one of the world’s biggest banks, Credit Suisse, narrowly escaped annihilation when it was bought by an even bigger Swiss bank, UBS Group, in a government-brokered deal. The hasty move did the job of averting the “too big to fail” lender’s, well, failure. But in the aftermath of the insolvency panic that triggered the falls of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank in the U.S.—not to mention the current precarious standing of First Republic—it’s fair to say that the world’s financial institutions, and their customers, are spooked.

Shaky confidence in global financial markets could spell further trouble, potentially setting off a massive cascade of bank runs that destabilizes the entire system. Right now, that possibility is not off the table. But is it a crisis?

“I would say no,” Arthur Dong, an economics professor at Georgetown University, says. But we’ve gotten a preview of what could happen next, he told me.

In short: After years of very low interest rates, the decision in the U.S. and elsewhere to begin raising interest rates in order to curb inflation led to lowered asset value. That, in turn, led to depositors’ whisperings of relocating their holdings and not-totally-unwarranted fears of bank insolvency. For SVB, and other lenders that similarly serve a narrow band of customers (who are likelier than a more diverse pool to react in unison to market shifts), these conditions can add up to a major stress test of client confidence. And as SVB has shown, bank failures don’t exactly alleviate wider anxieties—even if federal governments and regulators step in to protect customers’ holdings, as was the case for SVB.

Dong acknowledged that, although the sagas of SVB, Credit Suisse, et al., have certainly created “shock waves through the financial markets” (and inspired worry in the average consumer about whether their deposits are safe), the present climate of economic uncertainty is probably more aptly viewed as a momentary shake-up than an existential disaster. “There are other institutions out there that might be imperiled, in the way that SVB was imperiled, but I don’t think it’s a global crisis,” Dong explained.

But although it isn’t a full-blown crisis, it might be a “mini-crisis,” suggests Paul Kupiec, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. “Could it get worse? Yes. Could it be just a bump in the road that goes away? Yes.”

Kupiec says that if the Fed continues to raise interest rates, many institutions’ mark-to-market losses will get worse. More people might be moved to pull out their deposits, which could have far-reaching consequences—especially if multiple banks find themselves in a position of needing to replace those deposits (that they’d collected minimal interest on for a long time in the first place) with Federal Reserve loans whose target rate range is already 4.5 to 4.75 percent, and projected to climb higher.

“We’re not totally out of the woods,” Kupiec told me. “We might avert a panic. There’s going to be some pain going forward, though.”

“This is what happens in this type of environment with higher degrees of volatility, as well as very rapid interest-rate increases around the world,” Dong noted. “And it will very quickly expose the weaknesses of banks that were not necessarily in a state of failure, whose balance sheets were kind of creaky to begin with.

“As the tide goes out, you kind of see who’s swimming there naked,” Dong added with a chuckle, borrowing a well-known aphorism from the investor Warren Buffett. “I think that’s more of the issue here, rather than a widespread or global financial contagion like we saw in 2008.”

For now, we can expect more damage control. Earlier today, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen told a conference of American bankers that she was willing to protect depositors at smaller U.S. banks in the event of future bank runs, if necessary.

We can’t know what will happen next. But the picture of what’s happened up to this point, and how to read it, is coming into focus. As my colleague Annie Lowrey wrote last week on the SVB collapse and bailout:

There’s no success story here. The complexity of financial regulations and the dullness of balance-sheet minutiae should not lull any American into misunderstanding what has happened. Nor should the lack of a broad meltdown make anyone feel confident. The bank failed. The government failed. Once again, the American people are propping up a financial system incapable of rendering itself safe.

Related:

Today’s News

- Classes for nearly half a million Los Angeles students were canceled as bus drivers, custodians, cafeteria workers, and other educational-support workers launched a three-day strike.

- Surveillance video from a state psychiatric hospital in Virginia shows a group of staff and sheriff’s deputies pinning a Black man named Irvo Otieno to the floor for about 11 minutes before his death.

- Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin declared their economic partnership and signed 14 agreements.

Dispatches

- Work in Progress: Derek Thompson argues that all the ChatGPT predictions are bogus.

Explore all of our newsletters here.

Evening Read

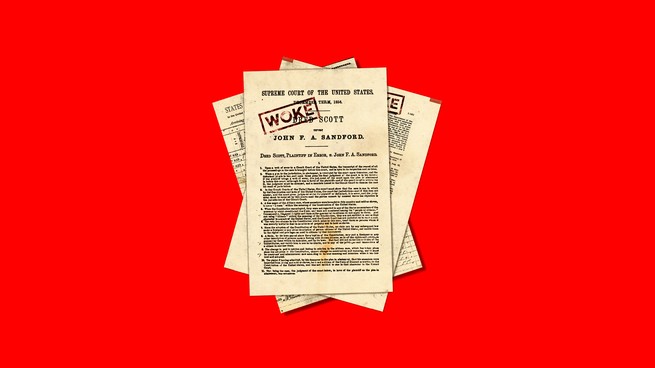

Woke Is Just Another Word for Liberal

By Adam Serwer

The conservative writer Bethany Mandel, a co-author of a new book attacking “wokeness” as “a new version of leftism that is aimed at your child,” recently froze up on a cable news program when asked by an interviewer how she defines woke, the term her book is about.

On the one hand, any of us with a public-facing job could have a similar moment of disassociation on live television. On the other hand, the moment and the debate it sparked revealed something important. Much of the utility of woke as a political epithet is tied to its ambiguity; it often allows its users to condemn something without making the grounds of their objection uncomfortably explicit.

More From The Atlantic

Culture Break

Read. Rebecca Makkai’s novel I Have Some Questions for You probes the line between justice and revenge.

Watch. Living (available to rent on multiple platforms), a movie by Kazuo Ishiguro that interacts richly with the universe of his novels.

P.S.

If the current banking saga has you scratching your head, or you’re asking yourself why global finance seems kind of made-up and strange, I have the book for you—Filthy Lucre: Economics for People Who Hate Capitalism, by the University of Toronto philosophy professor Joseph Heath. Don’t be fooled by the title; you don’t need to hate capitalism to appreciate Heath’s reasoned, ideologically balanced takedown of a dozen beliefs (or as he frames them, misconceptions) about the global free-market system.

When Filthy Lucre came out in 2009, I was a college super-senior preparing to graduate from the University of Toronto and into the roaring global recession, a fluke of timing I would not recommend. Several of my friends had been students of Heath’s, and a copy of his book made its way onto my shelf. That hardcover edition was lost to the years. But lately, I find myself wanting to revisit it.

— Kelli

Isabel Fattal contributed to this newsletter.