From borders to Cold War politics, factors that shaped 75 years of India-China diplomatic relations

How have India and China responded to moments of crises and the potential for cooperation in bilateral ties? What can happen going forward? Official records and statements, as well as commentary from India’s top diplomats who engaged with China, offer some insights.

(Left) Chairman Mao Zedong of the Chinese Communist Party and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. In April 1954, when Nehru visited China; and PM Narendra Modi and Chinese PM Xi Jinping in 2016. (Wikimedia Commons)

(Left) Chairman Mao Zedong of the Chinese Communist Party and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. In April 1954, when Nehru visited China; and PM Narendra Modi and Chinese PM Xi Jinping in 2016. (Wikimedia Commons)On April 1, 1950, India became the first non-socialist bloc nation to establish diplomatic ties with the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

These were the early days of the Cold War, when the world was mostly divided into two camps. The communist Chinese state under Mao Zedong had been set up just six months ago, after a bloody civil war.

The “non-aligned” India under Jawaharlal Nehru had reasons for reaching out to China — the two had much in common, both ancient civilizations emerging from a long and repressive colonial rule. In his writings, Nehru referred to China as “India’s old-time friend”, admiring its rich culture and history.

The initial enthusiasm notwithstanding, the ties were marked by mutual distrust and differences over the 3,000-km shared border early on. The 1962 war — independent India’s only military defeat — marked the lowest point of the ties.

However, the countries’ proximity means each trough has been followed by attempts at reconciliation between the “elephant” and the “dragon”.

Today, their formidable economic positions have kept alive the potential for engagement, even after infractions like the 2020 standoff in Ladakh. In FY 2023-24, China was India’s biggest trading partner.

How have the two countries perceived each other? Official records and statements, as well as commentary from India’s top diplomats who engaged with China, offer some insights.

Seeds of distrust

China had refused to abide by the British-era Simla Agreement of 1914 that outlined areas of control, including the McMahon Line as the border between Tibet and India. Nehru hoped that forming ties early with the PRC would lead to goodwill in negotiating the contentious border question. For China, a relationship with India could improve its heft among decolonised nations, thanks to India’s existing ties under the non-alignment banner.

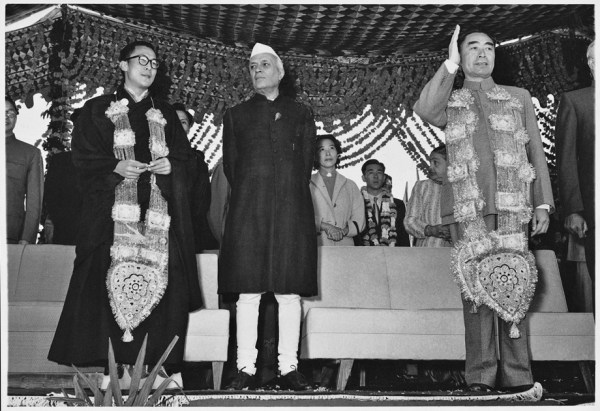

The Dalai Lama, Nehru and Zhou Enlai in 1956 in India, at the UNESCO Buddhist Conference in Ashok Hotel, New Delhi. (Wikimedia Commons)

The Dalai Lama, Nehru and Zhou Enlai in 1956 in India, at the UNESCO Buddhist Conference in Ashok Hotel, New Delhi. (Wikimedia Commons)

Vijay Gokhale, former Foreign Secretary and Indian Ambassador to China, in his book The Long Game: How the Chinese Negotiate with India, wrote that India may have squandered certain advantages by quickly agreeing to China’s pre-conditions and offering none of its own.

For instance, China made accepting the One-China Policy non-negotiable, meaning India could not acknowledge Taiwan as an independent nation. However, for Chinese leaders, India remained a suspicious entity. Its decision to maintain relations with countries like the UK was seen as betraying weakness and allowing Western influence.

In India, China’s invasion of Tibet in October 1950 raised serious concerns. Deputy Prime Minister Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel told Nehru that China should be viewed as a potential enemy, but Nehru was not convinced. In 1954, the Panchsheel Agreement was signed, outlining five core values to guide bilateral ties: respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty; mutual non-aggression; mutual non-interference; equality and mutual benefit; and peaceful co-existence.

This was tested to its limits in 1959, when anti-China riots broke out in Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, and the Dalai Lama was given sanctuary in India. This “convinced the Chinese leadership that India was engaged in subverting Chinese sovereignty over Tibet,” wrote former Foreign Secretary Shyam Saran in How China Sees India and the World. Border skirmishes since then added to the sense of strategic threat.

The aspirations of “Hindi Chini bhai bhai” (Indians and Chinese are brothers) and Panchsheel could no longer be reconciled with the actual state of the ties. When war finally broke out in 1962, India lost more than 3,000 soldiers and around 38,000 sq km of land in Aksai Chin.

Great power triangle

These early interactions formed the basis of a complicated relationship, with borders being just one of the determinants. In a 2022 working paper for the think tank Carnegie India, Gokhale argued, “China’s India policy has been shaped by its view of the larger great power strategic triangle of China, the Soviet Union (later Russia), and the United States.”

Somewhat paradoxically, China perceived India as a competitor for security and status in Asia but simultaneously saw it as an unequal player. Many Chinese foreign ministers or leaders made no mention of India in their writings. Post-1962, India’s growing ties with the USSR became a concern for China as its own relations with the Soviet Union became fraught. This also prompted it to deepen its relationship with Pakistan.

Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s visit to China in 1988 led to a thaw. Deng Xiaoping, then Chinese President and architect of the landmark 1978 economic reforms, said an upcoming “Asian Century” could not be realised without India and China developing. Gandhi, on his part, reiterated that India was unwilling to give up any more of its territory.

By then, significant shifts had occurred — deaths of Nehru and Mao, China’s economic liberalisation, the establishment of US-China diplomatic ties in 1979, and the accession of Sikkim into India in 1975 (which China refused to accept). China and India also conducted nuclear tests in 1964 and 1974, respectively.

The year 1991 marked a watershed, with the USSR disintegrating and India taking steps to liberalise its economy. In his book Choices: Inside the Making of India’s Foreign Policy, former Foreign Secretary Shivshankar Menon wrote: “The collapse of the Soviet Union made old foreign policy certainties invalid… It was time for something different in India-China relations… It seemed logical that in these circumstances, it would serve both Chinese and Indian purposes to try to impose peace along the border while leaving to the future the more politically difficult task of settling the boundary.”

Menon was part of the negotiations for preserving the status quo on the contested Line of Actual Control (LAC) in the western sector. The Border Peace and Tranquility Agreement was signed in September 1993 during then PM Narasimha Rao’s visit to China. “This was a big decision for India, where public sentiment was still aggrieved by the defeat of 1962,” Menon wrote. He credited Rao’s “cold calculation of national interest and his ability to quietly persuade his political allies and opponents.”

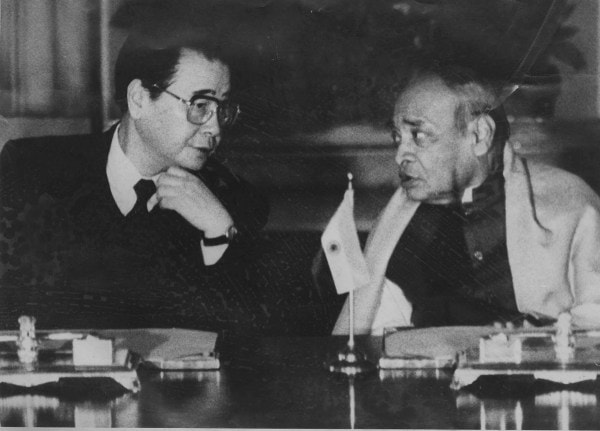

Li Peng, Premier of China, with Prime Minister PV Narsimha Rao. (Express archives)

Li Peng, Premier of China, with Prime Minister PV Narsimha Rao. (Express archives)

The agreement mentioned confidence-building measures and restrictions on military exercises near the LAC. The provision on keeping troops near the LAC at a “minimum level” based on “mutual and equal security” is yet to be explored.

Dragon races ahead

At the dawn of the 21st century, India and China were poised to become major economic powers. Several initiatives were then taken to improve bilateral ties, such as establishing a Special Representatives mechanism in 2003 and China’s recognition of Sikkim as part of India the same year.

However, the divergence in their economic trajectories soon became difficult to ignore. From 1987 to 2023, China’s economy grew from $272 billion to $17.7 trillion, while India’s increased from around $279 billion to $3.56 trillion.

Saran wrote that unofficially, Chinese scholars would speak of China’s growth and imply that “India should accept its diminished ranking” and “defer to Chinese interests.”

Challenges, lessons

Today, the geopolitical landscape is the least predictable it has been in decades. China, however, seemingly continues to treat bilateral ties with India as part of its wider tussle with the US. For Beijing, establishing Chinese domination is a national rejuvenation project following its “Century of Humiliation” at the hands of colonial powers. Thus, India’s friendly ties with the West, especially the US, are an irritant for China.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping before delegation level talks, in New Delhi in 2014. (Express archives)

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping before delegation level talks, in New Delhi in 2014. (Express archives)

For India, there are lessons in China’s rise. Its “single-minded promotion of its human resources through quality education at all levels” and its investments in physical infrastructure are worth emulating. But India can aspire to a “different strategy of growth which is ecologically more sustainable and may offer a more attractive model” (Saran). Improvements in India’s military preparedness, especially in the Indian Ocean Region, is also crucial. “In meeting the China challenge, India will need to build on its relatively stable polity and the inherent cultural assets it possesses. The rise of narrow nationalism, the deliberate stoking of communal discord and the attempt to put up a monochromatic frame over a diverse country… devalue the very assets which make India distinctive,” Saran wrote.

Looking ahead

Meaningful cooperation would require significant changes in China’s views about India. The LAC standoff in 2020 dispelled the notion that India would not escalate militarily in response, and there is a sense of clarity among policymakers, wrote Gokhale. Globally, too, countries in Southeast Asia and elsewhere have lodged clear opposition to Chinese expansionist tendencies.

At the same time, it is “untenable that two major Asian countries that are also neighbors as well as nuclear weapon states refrain from conversations about the state of their relationship,” wrote Gokhale.

Within the last year, some efforts towards normalisation of ties have been visible, with Chinese President Xi Jinping meeting Prime Minister Narendra Modi in October on the margins of the BRICS Summit in Kazan, Russia.

What shape these efforts take remains to be seen, but at the 75-year mark, there continues to be room for both caution and conciliation in India-China ties.

More Explained

Must Read

EXPRESS OPINION

Apr 10: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05